Peter Warshall (1940-2013) was an interdisciplinary ecologist, essayist, and self-described “maniacal naturalist” with a particular enthusiasm for ornithology, hydrology, pedology, and primatology. Trained at Harvard as a biological anthropologist, he was the natural systems editor for the Whole Earth Catalog and the editor of the Whole Earth Review for a decade. He was an expert on topics as varied as the ecology of septic systems, the Mount Graham red squirrel, sky island ecosystems, and the evolution of the planet’s visual and vocal ecologies. He designed the Savannah ecosystem and invertebrate food web for Biosphere 2; worked as a natural resource and biodiversity management consultant for USAID, the United Nations High Commission for Refugees in Ethiopia, and the Tohono O’odham and Apache Nations; and regularly taught ecopoetics at the Jack Kerouac School for Disembodied Poetics. With his wife, the historian Diana Hadley, he helped found the Northern Jaguar Project, a 56,000-acre reserve in the US-Mexico borderlands protecting the critical habitat of the northern jaguar and other threatened flora and fauna.

Nicknamed “Dr. Watershed”, Warshall was perhaps best known for his extensive work on water and watersheds. Throughout his nine-year stint in public office at the Bolinas, California Public Utilities District (BPUD), he administered projects on watershed management, pasture irrigation with recycled water, constructed wetlands, water rights and conservation, home-site sewage systems, water quality risk assessment, and drinking water supply. This work culminated in the publication of the appropriate technology classics Drum Privy Guidelines (1973) and Septic Tank Practices (1979). In 1976, Stewart Brand invited Peter to guest-edit a special issue of the CoEvolution Quarterly on “Watershed Consciousness”. His “Streaming Wisdom” title essay and famous “Watershed Quiz” helped initiate the local watershed governance and protection movement.

Warshall, Peter. Septic Tank Practices, A Guide to the Conservation and Re-Use of Household Wastewaters, 1973.

Warshall’s essay “Watershed Governance” which was first published in the MIT Press anthology Writing on Water in 2002, discusses various issues related to managing watersheds and water resources. A freewheeling eco-pragmatist manifesto that was far ahead of its time, the essay highlights different scenarios where disputes and rivalries can arise over water sources, water usage privileges, and damaged or degraded water supplies. Warshall emphasizes the need for institutions that promote transparency, accountability, and fairness in water management, concluding with a practical checklist for creating such institutions. He argues that the best stewards of water resources are Maniacal Water Watchers, capable of closely monitoring rainfall, river courses, and water consumption. Their diligence ensures that water and governance remain effectively intertwined, and they apply the wisdom of water to governance principles, emphasizing qualities over quantities, adaptability, and equality in the realm of watershed management.

Parker Hatley

The first collection of Peter’s essays and lectures, Squirrels on Earth and Stars Above, will be published in December 2023 by Edition Hors-Sujet (Zürich).

WATERSHED GOVERNANCE

Checklists to Encourage Respect for Waterflows and People

By Peter Warshall

The rain falls on the just

and the unjust fella,

But mainly on the just ’cause

the unjust got the just’s umbrella.

For watershed governance, you need the discipline of working rules and a good sense of humor. Admire humans and their leaky canteen-like bodies, and gently, firmly cover their greedy mouths before an insatiable thirst destroys the town. For where there are enough humans and not enough water, hydro-squabbles spew forth. Mark Twain, as usual: “Whiskey’s for drinking; water’s for fighting.”

I served as an elected director of a utilities district for eight years which meant endless hours wondering how local humans fit into watersheds. During this period and a subsequent twenty years as consultant, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, I can’t think of any aspect of waterflow that citizens didn’t doused me with—dam building or dam removal; water wrung from clouds or water pumped from depths; water exclusively for humans; water exclusively for birds; disgustingly dirty water; bottled water of questionable purity, or flush toilets of questionable efficiency. It’s all been important: a lake to preserve the reflection of the moon; cattle slobber in the feedlot; the unexplained healing powers of water in a steam bath or swimming pool.

I lucked out as a politician and, on a local level, helped build a totally recycling sewage system with prodigious artificial wetlands; encouraged self-sufficient home-site sewage systems; and insured pure drinking water. Political promises — clean and cheap water, an adequate supply for community desires, and a fair share for all (farmers, householders, bird watchers and retailers) miraculously worked out. But, elected office taught that water governs town life more profoundly than cheap and clean supplies. Waterflows, for instance, governed housing densities and town growth patterns. Citizens laughed cynically at zoning rules which appeared to change with each election. In their eyes, planning commissions and their representatives were fickle (if not corrupt in a sophisticated manner). But, a small diameter pipe that limited waterflow, limited water supply, and guaranteed limited sprawl. Waterflow shaped the town. Citizens refused to approve bonds for bigger dams to increase supply or wider pipes to deliver more water. They saddled the town government with a fourteen year law fight. But, the cost of litigation appeared more desirable than the cost of new waterworks and housing growth. So citizens insisted that water and truth be tightly tied. Truth-as-repetition-truth could not sway them. They did not believe that the more an authority said something, the more it must be true. They did not believe, as repeated many times, that zoning managed housing growth and land use patterning. The truth they came to was truth-as-it-always-is-truth. Waterworks shape the lives of watershed communities.

It was a time when this kind of skepticism sprang up in many communities. I remember Nassau County, Long Island citizens had been told by media and experts that their poor quality drinking water stemmed from too many failing septic tanks. It was repeated endlessly with the normal parading of experts. The citizens voted millions to replace the septics with a modern sewage treatment plant, only to discover that, sewering allowed greater housing densities, and the poor water quality came from pet dogs that pooped in local flood control basins. Doggie scoops would have solved the problem.

Like myself, each citizen I’ve talked with — about voting, protesting, lobbying or occasionally thanking their elected representative – has, at one time or another, turned inward, reflected on his/her feelings and intentions about water. Their images and memories of waterflow have applied a kind of aqueous moral pressure, an insistence within their selves to act, make a choice for the human community, and, by extension, the watershed. This essay elaborates a package of checklists, almost one-liners, that became important in considering water, this moral pressure, and its power.

Out wriggles the first salient truth: water creates an inescapable contract. We cannot choose to be part of its flows. Our bodily plumbing is always linked to the biosphere’s. We may live upstream or downstream; right bank/left bank; drink surface or groundwater; seed clouds or fish in a river; wash city streets or feed a cooling system to regulate the temperature in a nuclear power plant. In all actions, we never free ourselves. Water is biospheric life-support married to the laws of thermodynamics with no divorce clause. This inescapable hydro-contract leads to an inescapable social contract: we need working rules to maintain hydro-harmonies.

The Nature of Water and Watershed Governing

Before discussing hydro-contracts and their working rules, consider how water governs itself. Bemused awareness of water’s “self-governance” must always be first on the agenda as waterflows have a mischievous way of subverting and toying with our specie’s meager abilities at foresight Deny or fight waterflow’s always-true-to-itself-nature and pesky water nymphs stir up trouble. The Romans were so impressed that they considered free-flowing water a wild animal. Only captured water — like a caged animal — was subject to law.

Here are a few personality traits of water’s wild anima:

- Water is ethically neutral.

- Water has its extreme moments.

- Water is bulky, erratic, mobile, evasive.

- Water transforms without permission, assimilates organic and inorganic chemicals into itself more than any other substance on the planet.

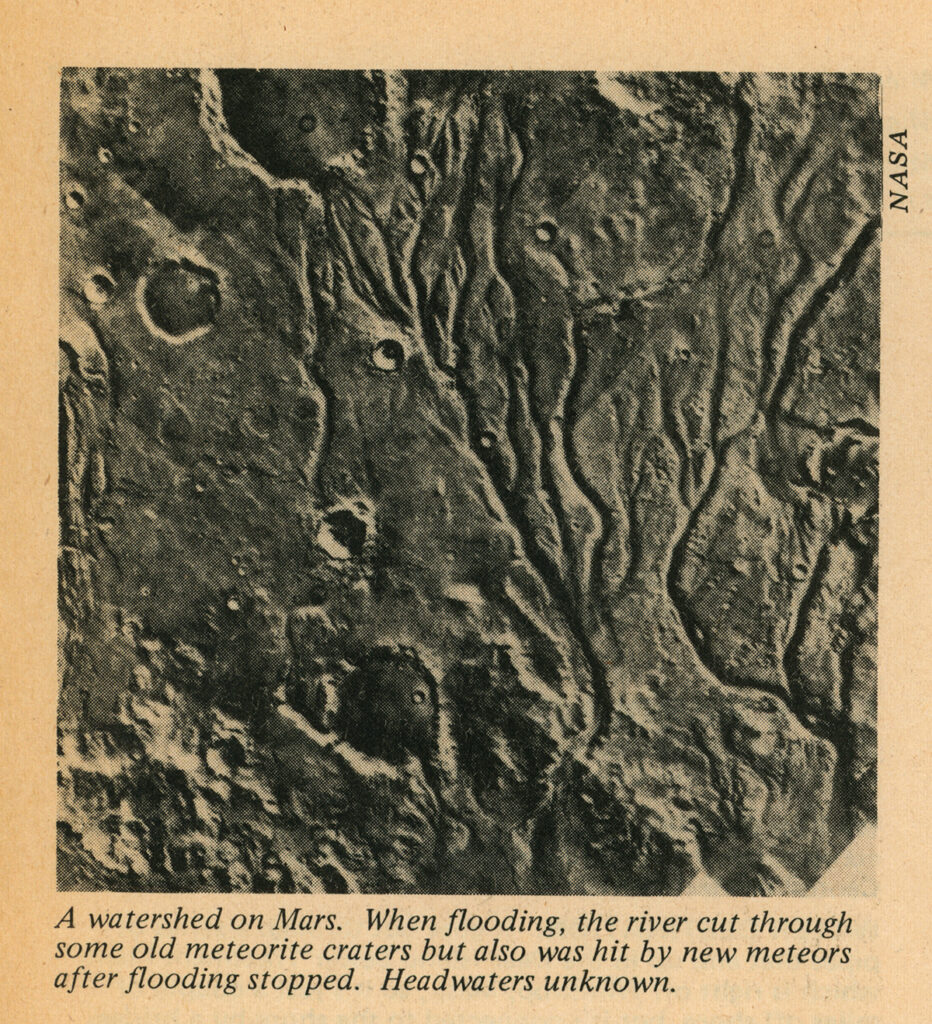

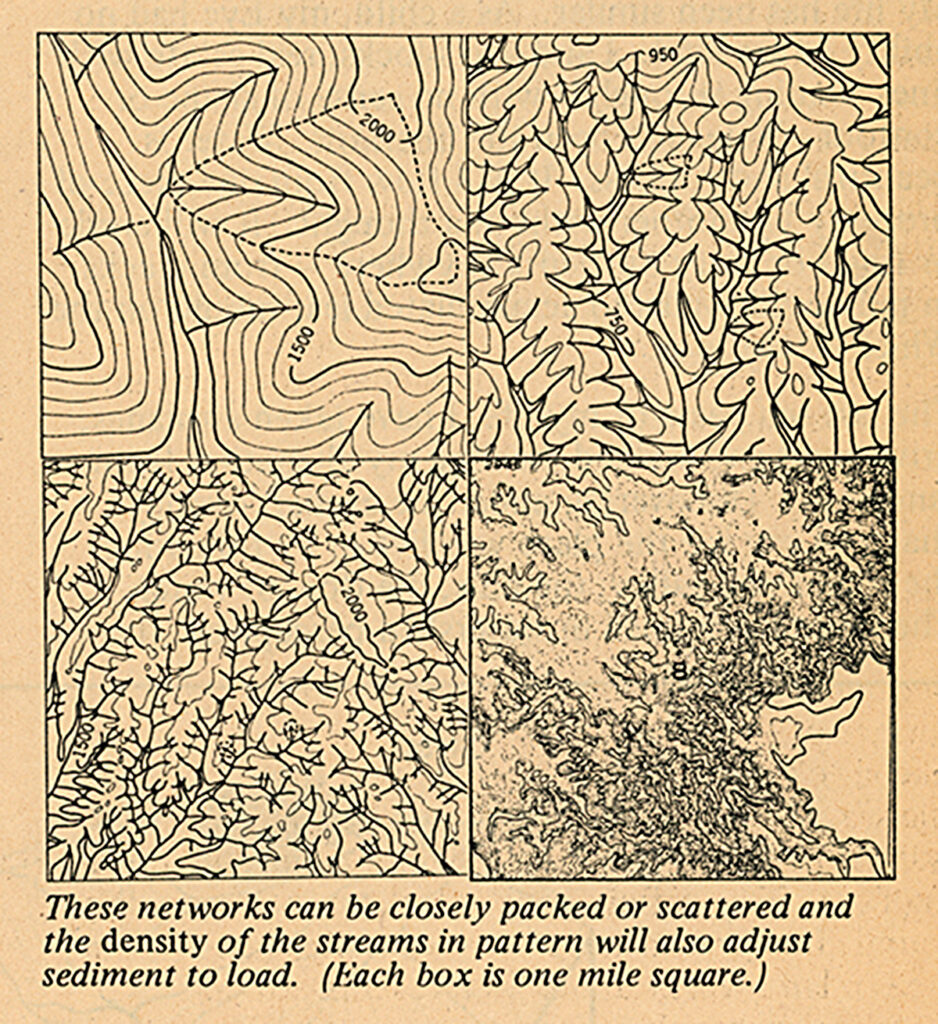

Illustration from Warshall, Peter. “Streaming Wisdom: Watershed Consciousness in the Twentieth Century,” in CoEvolution Quarterly No. 12, Winter 1976/77, ed. Peter Warshall. Courtesy of Stewart Brand

Water is neutral. Its indifferent. Waterflows don’t care if they are polluted or clean, flooding or trickling; in the President’s semen or the sweat of the Pope’s benediction. Water is an anarchist. Water blithely ignores property boundaries on land, underground, and at sea or in the atmosphere. Fickle water nymphs confound the best and worst of serious ethics — a slave in Missouri watched a flood alter the river’s course, and woke up a freeman in Kansas. Because of water’s neutrality, human rules about access to and use of waterflows must be very clear. Not for water’s sake — water will do what it does — but for human comfort and the sake of other living creatures which human water management influences.

Water has its extreme moments. Droughts, floods, blizzards and turned-over lake bottoms cause obvious suffering and pain to humans and other planetary creatures. Yet, hydro-extremes must be considered normal in all watersheds and in all hydro-compacts. Buffering or reducing the intensity and frequency of hydro-extremes is a modern human obsession. We don’t like waterflow’s dramatics. We just won’t tolerate them. Waterworks to tame waterflow is perhaps the most capital intensive, property contentious and socio-economic inequitable aspect of watershed management (Narmada, Yangtze, Bio Bio). Water could care less.

Water is erratic, mobile, and evasive. Even without extremes, water has a maddeningly contrary nature. On the mid-reach of the White Nile, the Dinka teach this aphorism:

Spring rains in a dry spell.

Drops club ants on the head.

And the ant’s say: It’s gods’ work.

And they wonder whether it helps.

And they wonder whether it injures.

Waterflows, for instance, disappear as groundwater, or evaporate as vapors just when you need them, and when you least expect it. Rivers change course despite billions of dollars of flood control channeling. Much of modern water politics – its civil engineering hopes and optimistic forecasts — starts with a denial of aqueous unruliness. In the US especially, we are a very “solution” oriented culture; yet water sticks its tongue out at our idealism and pragmatic pride. Sign a contract for long-term water delivery and the rainfall pattern mutates, rendering the contract irrelevant (Colorado River).

Water is equally unruly because it transforms quality without permission, assimilates organics and inorganic chemicals into itself more than any other substance on the planet. Water is the great absorber, adsorber, and biochemical renovator. Sometimes too salty or muddy or rich in nutrient. Sometimes too radioactive or brimming full of the emotions of local history. Count on drinking from a well and then find strange toxic brews showing up from unexpected sources (Tucson groundwater). Farm for maximum corn yields and discover that the runoff has killed off the fishing industry (lower Mississippi). In watershed governing, the price of water is not water itself, but increasingly the price to maintain its beneficial qualities. Drinking water and wastewater treatment and desalinization are governance issues because every gallon needing purification, needs energy and equipment to purify it, and equipment and energy have a cost (Middle East, Yuma).

Water is bulky and heavy. In the US, the weight of deliberately transported water exceeds the weight of all freight moved by railroads, barges and trucks. The price of water is, in many river basins, the price to move it. Governance, for instance, now includes moving water hundreds of miles from the Colorado River to six major jurisdictions (California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Mexico). Pumping this much water over mountain ranges in an open aqueduct that concentrates the salts requires energy both for lifting and for purification. The infamous aphorism of California— “Water flows downhill, except when it flows uphill toward money” — puts the unholy triumvirate of river basin governance into one sentence. Waterflow, the energyflow to move it and purify it, and the cashflow to pay for it, all spring from water’s bulky weight, its resistance to cheap transport as a liquid, and its perverse acceptance of what life dumps into it.

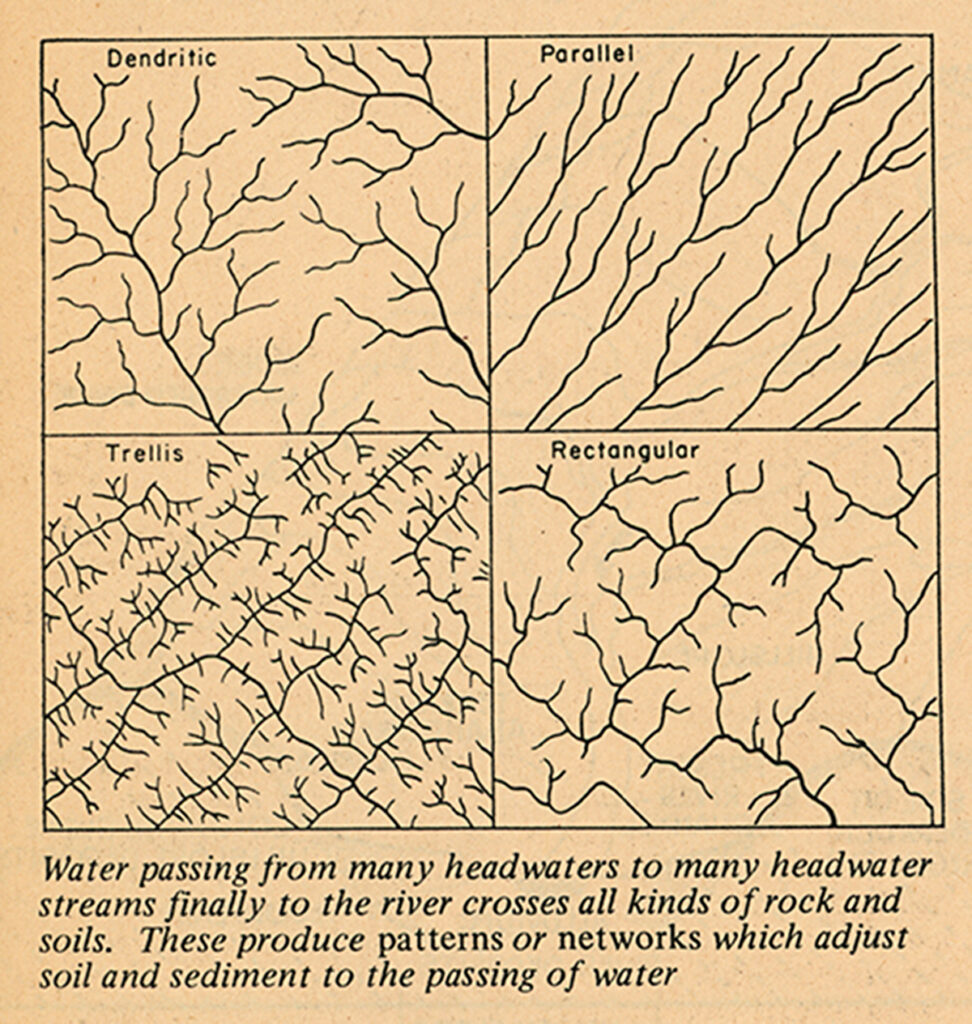

Illustration from Warshall, Peter. “Streaming Wisdom: Watershed Consciousness in the Twentieth Century,” in CoEvolution Quarterly No. 12, Winter 1976/77, ed. Peter Warshall. Courtesy of Stewart Brand

The Human Life of Water

If water itself was not such a pain to deal with, then stirring in human feelings about water will surely drive watershed citizens, leaders, and managers to drink. Elected officials, planners, engineers, fishers, wild rice gatherers, duck hunters, wetland birders, swimmers, water skiers, riparian restorers, women water carriers, barge captains, wastewater treatment plant operators, canal and irrigation ditch workers, farmers, fire managers, plumbers, homeowners can all lose track of hydro-essentials: that respecting water with all its contrary and mischievous behavior is the touchstone of a kind politics.

Here’s the second course of priority aphorisms for those who dare mix water-thought and a big heart for their human communities.

- Water is life.

- Water is precious – a strategic resource in the maintenance of social cohesion.

- Water is deeply embedded in watershed landscapes; is tenaciously site-specific.

- Water is more than a commodity with production value.

Water is life. Like liberty and the pursuit of happiness, minimal hydro-security is a basic human right. A healthy water supply supersedes all other economic and legal dictates. «Our bodies are but molded water» (Novalis). When the minimum vanishes (as in the Sahel after sixteen years of drought), all sense of compassion toward the landscape, other humans or non-human creatures fades. Hydro-security is a two to three day proposition. Without water, thieves, beggars, migrants and rioters emerge from the dust. We forget. We are lucky; we forget. Water First!

(This essay assumes watersheds with a basic water supply. To give proper attention to crisis watersheds and human coping strategies, it’s just another endeavor.)

If water is essentially the blood of our lives, it is also the blood of non-human species and productive habitats. Although honoring biospheric life-support is not common to the majority of humans, there are early indicators that, in the future, the pursuit of human happiness will also insist on water supplies for flora and fauna. Water, without much of a stretch, can be seen as the basic right of all living creatures.

Water is precious – a strategic resource in the maintenance of social cohesion. «‚Til taught by pain, man knows not water’s worth» wrote Byron as he traveled into the more arid lands of Greece then Turkey. Deserts and droughts were stark teachers. In Morocco, death can be the penalty for wrongful use of an oasis or allowing non-assigned goats to eat leaves from wadi trees. In the contemporary Jordan/Syria/Israel river basin or Ethiopia/Sudan/Egypt basin of the Blue Nile, hydro-balances are delicate and water sings a military tune. Destroying waterworks is the ultimate card to be played in the poker game of diplomacy and war.

Even in times of peace, every recipe for every good and service of value to human societies says: add water. All energy (coal, nuclear, hydro, wind, diesel, geothermal) depends on water. Waterflows drive the planet’s green machine, churning out food and entering all product development from computers to underwear. Waterflows provide free community services: modifying climate, aerating and purifying waterflow as it rushes down rivers, biochemically renovating pollutants, providing a medium for fish to grow. Agricultural, industrial and information–based societies all require incredible waterworks. From the Fertile Crescent to the Yangtze of China to the American West, “hydraulic civilizations” have come and gone with the ability of their governors to keep water flowing to their constituents without unexpected harms.

Water is more than a commodity. Water bodies are great sources of joy. Sloshing around in tanks, ox-bows, swimming pools, and creeks nurtures giggles; sitting by the ocean quiets the soul, and steam baths and jacuzzis heal with still unexplained powers. In our dreams, reflections, and stories, water as perhaps no other substance gushes with beauty, spirit, grace, and long-term community life.

In short, in watershed governance, water’s price is only a part of the picture. Sometimes a very small part. Purely economic models will never suffice. For instance, economic analysis often plays second or third fiddle to cultural stubbornness. American love of golf has, in many law cases, insisted that water to irrigate the green is a higher and better use than an in-stream flow for an endangered trout. Or many Hindus insist that bathing in the Ganges must be healing despite their exposure to water-borne disease.

Non-consumptive uses like leaving enough water in a river for swimming and fish conveyance have indirect, difficult to assess, economic benefits. They drive politicians, who like cost/benefit analyses, bananas. Yet all watershed governance must include allocations that may have no apparent financial value such as enough water to preserve the simple reflective beauty of lakes. In the parlance, hydro-beauty has a non-monetary existence value.

That flowing water! That flowing water!

My mind wanders across it.

That broad water! That flowing water!

My mind wanders across it.

That old age water! That flowing water!

My mind wanders across it.

— Navajo, The Mountain Chant myth

In summary, as opposed to other flows (cash, info bits or energy), waterflows are hard to model, stylize or generalize. To the great frustration of human dreams and reason, waterflows are maddeningly site specific, embedded in unique watershed landscapes. The ways watersheds gather, store, channel, schedule, disperse, concentrate, dilute and biochemically transform water quality depends on details — the specific weather, the specific configuration of the aquifer, the specific flood pulse and channel width, the specific mass loading and concentrations of chemical ingredients. Where I live in Tucson, salts and pollutants concentrate as they descend downstream because of water losses from high evaporation. In my mom’s watershed (the Hudson), salts and pollutants dilute with each downstream tributary. In the more formal language, watersheds depend on situational variables more than aggregate or summary variables. Sit pleased as Punch with an aqueous generalization, ignore the individuality of a watershed’s persona, and the waterflows will play you for a sucker

To harmonize watersheds and their human communities, Watershed Mind learns to be humble, intellectually insistent, and soulfully patient. It is hard work and the “uncertainty principle” thrives in water. How many times have engineers spoken with solemn precision about a creek’s design flow and with equal solemnity about its water quality, convincing a utilities board of its grasp on reality; and how many times has some other aspect of water’s contrary nature or watersheds’ surprising adjustments eluded our mental picture.

Governing bodies spend much of their time dealing with the unintended consequences of earlier «solutions» to their watershed’s management problems.

Watershed Rivalries

«Rival» comes from the Latin word rivalis, meaning «river.” In the Hollywood version, two groups of cave men scream and prance on opposite banks brandishing stick spears. The river is the rule, the no trespass sign. But, outside Hollywood, watershed rivalries come in many more flavors. Sometimes people fight over access to water sources; sometimes they agree on access but fight over use privileges (how much and when can be it taken); sometimes they fight over a damaged or degraded supply. Sometimes, as the Taos pueblo fight over sacred Blue Lake, they fight to keep a body of water untouched.

For aqueous contemplation, here are a few simplified post-caveman rivalries:

- A sewage plant treats the wastewater from a town and then sells the treated wastewater to a golf course. It uses the revenue to increase the size of the treatment plant, anticipating new customers. The residents protest. They claim the wastewater was theirs and the profits from selling the water to the golf course should go toward reducing their monthly fees. A conservationist group also protests claiming that the treated wastewater (discharged into a creek) had supported a wetland bird sanctuary and, once dedicated to the creek, was no longer the property of the wastewater treatment plant. It should neither be sent to the golf course nor used to reduce sewage fees. This is typical: cultural, environmental, investment, history, water re-use confusions. How to navigate?

- A water company has impounded a stream for hydro-electric production and only releases water when power is needed. This causes the fish population to crash. Trout fishermen sue and demand a more even release — no matter what the demand for power. The company says that the fisherman can have the water if the pay the equivalent of lost revenues. The fishermen say that the water rightfully belonged to the stream first and, if the company refuses to release waterflow to help maintain the fish, the hydropower company should pay damages. Who wins?

- A farmer has spent time and money installing water conservation equipment and has cut his water use by 35%. But, he has no additional land so he now leaves 35% more water in the river. He claims that this is his water (by previous use) and wants the downstream farmer who has more land to pay him for it. The downstream farmer refuses because the upstream farmer has not «used» the water left in the river nor transported it to him by pipe. The upstream farmer lost his property right for being a good citizen.

- A series of farmers pump out groundwater, lowering the level of a spring so it no longer flows. A Native American group claims the spring is sacred, a crucial element of their healing ceremonies and spiritual needs, and part of their cultural heritage. Because the spring has no «development» associated with it, the law states that it is not the «property» of the tribe. Unless the Indians can demonstrate prior use of a specified volume of flow, they cannot claim the spring. There are no written documents (only oral stories) supporting prior use and the volume consumed (compared to the outflow desired) is minuscule.

- An upstream sewage plant treats millions of gallons of urban water to the highest standards set by the government. This high quality effluent enters a salt water estuary and causes «osmotic shock» (the critters who thrive best in salty water are harmed by the influx of freshwater). A conservationist group sues to stop all discharges that might hurt an endangered fish, even though the treatment plant has performed better than all discharge requirements.

In a newly settled watershed, rivalries center on capturing and dividing unclaimed supplies and capital to build the waterworks. In industrialized nations, most waterworks have already been built and most water rivalries start when citizens and governments change water from agriculture to urban use; transfer waterflow between watersheds; divert more water from in-stream to off-stream, or from underground to aboveground uses; degrade water quality and damage downstream needs; subvert taxpayer senses of equity; require payment of damages from acid rain; or propose sewage and water pipes that influence housing growth.

In all rivalries, healing watersheds means healing the angers, ignorance and desires, if not bitterness, of watershed citizens. Its an old story, told in China centuries before the common era:

The sage’s transformation of the world arises from solving the problem of water. If water is united, the human heart will be corrected. If water is pure and clean, the heart of the people will readily be unified and desirous of cleanliness. Even when the citizenry’s heart is changed, their conduct will not be depraved. So the sage’s government does not consist of talking to people and persuading them, family by family. The pivot (of work) is water.

Lao Tse

A post-modern Lao Tse might carry this crib sheet to help dive to the heart of the matter:

- How much unclaimed or over-claimed water resides in the watershed?

- Are there scarcities by location, season or year?

- Which or whose vested rights predominate?

- Where are the watery places of special nature? Who are the aquatic non-human creatures that require protection? How much water is needed for non-consumptive uses?

- How much of the flow resides in the watershed’s natural ecostructures (its channels, wetlands, soils) and how much in the human-built infrastructure (its pipes, aqueducts, reservoirs, storm sewers)?

- What uncontrollable “externalities” (e.g., leaking groundwater, cloud seeding, climate change, interwatershed transfers) impinge on workable hydro- rules?

Institutions and More Institutions

Lao Tse’s great contribution to watershed governance was: always give priority to water over human special interests. No matter how charming human ideals, poetics, political rhetoric, divine revelations, promises or factoids, hydrophilia is the best consensus builder. I always check out a rival or ally to discover if he/she actually likes water; finds it both amusing and profound; knows water has its own way of being. If friend or foe do not cherish water, they are probably the all-too-common shuck and jive citizen-leaders who thrive only on the hydro-politics game (but not water-watching and water-love). Ultimately, no matter which side of the hydro-squabble, they will not have the skills to overcome special water interests.

The rarity of hydrophilia can be appreciated. Not for another 2000 years, with the birth of John Wesley Powell, did another human write as well as Lao Tse about hydro-communities and the skillful means to build hydro-harmonies. To achieve peaceful resolutions of water rivalries, John Wesley Powell and Lao Tse eventually needed to gather the community into a forum. Within these human “confluences,” the community’s working rules for waterflows emerged.

The intensely anthropocentric task of creating rules for human behavior is the heart-and-soul watershed governance. Citizens discover new rules by gossiping in the local café, walking the watershed, questioning authorities, adjudicating, arbitrating, mediating, casting their votes, and negotiating. Governments «institutionalize» their watershed rules in myriad ways: informal agreements, hiring a watermaster to arbitrate flows, electing utilities district regulators, forming a private corporation or a public water district, a sewer district or a river basin quasi-public task force, relying on state water departments, depending on federal agencies and so on. Institutions — broadly, the working rules agreed upon by a community — carry watershed sustainability.

In those nations where institutions are weak and public discussion prohibited, humans commonly kill each other over water deals. (The last US militarized water war was in l934 over the Colorado River. No one was killed.) Where watershed institutions are unfair or hopelessly out-dated, disenfranchised and angry citizens gravitate toward cheating on water allocations and stealing waterflow (especially at night). If pushed «too far,» embittered water users monkey wrench and obstruct by non-violence. The Umatilla basin in Washington is a classic example.

Uncomfortable with institutions that coerce humans to accept dictated waterworks (e.g., the Three Gorges Dam in China or Narmada dam complex in India) and imperially dictate waterflow rules, I have spent much of my watershed life trying to creatively destroy harmful watershed governance and institutions, and replace them with more responsive working rules. In a New Mexican watershed I recently visited, the state’s rules didn’t work. It was near impossible to technically deliver water to the priority rights holders then block up the irrigation canal for the next in priority (who was upstream), then re-open the floodgates for the next in historical priority. Water was lost; the process took too much time. It was too complex to remember. Quietly the watershed residents forgot the priority sections of the water law (keeping the volumes intact) and simply trusted the water master to let water out of the ditch in a fair and equitable manner. He had done so for over thirty years.

Local citizens, understanding the complexity of equity and the fickleness of local waterflows, have experimented with “shadow governments” — essentially creating institutions that do the job that the government or private utility should have been doing. Sometimes, when strong enough, members of these parallel institutions challenge competing special interest groups or hydro-bureaucracies. They move from shadows to daylight. That’s how I was elected.

Illustration from Warshall, Peter. “Streaming Wisdom: Watershed Consciousness in the Twentieth Century,” in CoEvolution Quarterly No. 12, Winter 1976/77, ed. Peter Warshall. Courtesy of Stewart Brand

In the early l970s, for instance, no working rules guaranteed waterflow inside the river channels of US watersheds. The salmon in the Columbia River basin and their human voices (fishers and Indians) could only bare witness and tell the tale. Slowly the fish and their human spokes-people gained legitimacy among the hydro-electric boys and the irrigators. They had to fight to join the small officious clique that dreamed up all the rules. They found themselves trapped by the past (impassable dams) and finances (the costs of fish ladders) and the old habits of the bureaucrats. What is fascinating about their now limited success is how much rested on their ethical arguments about fairness to fishers, treaty signatories, and the fish themselves; and their intimacy with the actual riverflows and fish runs. In Lao Tse style, the power of intimacy with their watershed partially overcame the power of money. When the dream — that it might be possible to rehabilitate past damages —took hold, the shadow governors began to re-shape the rules. Removing dams is now considered a reasonable alternative.

For those who are starting their first watershed shadow government, here, in the lineage of Mr. Powell and Elinor Ostrom (in her brilliant “Governing the Commons”), is a practical checklist. It’s long but it can save a lot of community heartache. If I’ve forgotten or missing an item, send it along for this essay’s next revision.

A good watershed institution

- opens its doors to public participation and insures that everyone has equal access to information.

- gives a priority to local watershed needs (the watershed of origin).

- has a well-defined degree of local autonomy so it can peacefully custom-design rules and change them, despite regional water budgets and ever-fluxing values of the culture.

- is accountable, competent, respects its own laws, adapts laws to water-years, finds the best local incentives and disincentives, and protects human rights.

- allocates a certain volume of flow to the private (competitive) sector, a certain amount to long-term stability (usually publicly enforced water rights), and a certain amount for existence value and basic human needs (untouchable by either the public or private sector).

- publishes the transaction costs of the institution.

- informs and asks watershed citizens about the harms and costs to downstream communities, to slope stability, to soil capital, to channel equilibrium, to water qualities, and to the flora and fauna within the watershed.

- informs citizens of the financial costs and benefits of each waterflow usage as a segment of the total cashflow of all watershed activities. Are there important multiplier effects? Is there any bonding capacity left?

Good watershed governors:

- Decide who is eligible to make decisions about watershed waterflows.

- Decide what actions are allowed or constrained, forbidden, required, permitted and encouraged.

- Set inflexible rules for basic water rights for both humans and in-stream flow. Set very flexible rules to preserve an arena of competition based on allocations for the highest price per gallon.

- Decide what «aggregation rules» will be used (the series of steps required to protect, challenge and change the rules).

- Decide what water-year procedures must be followed (emphasize incentives).

- Decide what knowledge (information and wisdom) must or must not be provided.

- Decide what payoffs and punishments will be assigned to individuals depending on their actions.

The Dr. Watershed Kit for Essential Watershed Governance

All things are dissolved by fire and glued together by water.

— Plato’s follower

Perhaps, this essay contains too many lists. One for water’s nature; one for human communities and water; one for good watershed governance; one for starting a shadow government. Consider them as points in a flowing river — pools and riffles, eddies, and the mainstream tongue. You can come back to them and sit there water-watching as needed. Here’s one more. A short list of “tools” that have helped me resolve water disputes.

The water-year. My favorite tool for promoting peace, flexibility and harmony is the «water-year» because, in any particular year of rainfall, only certain actions are possible and certain sacrifices must occur. This is the humbleness that water teaches. I learned about water-years in California. The state, by opening and closing dams, allows different volumes of flow into San Francisco Bay in any of five types of water-year: normal, dry, critically dry, wet, and super-wet years. While a myriad grumblings occur, everyone basically understands that you can’t apply the same rules to different volumes of riverflow. By framing governing guidelines by water-years, watersheds as different as industrialized San Francisco Bay or non-industrialized Lake Chad have begun to create flexible rules for community hydro-design.

Water efficiencies: The “easy” way for politicians to resolve water issues is to stretch the supply. They love consultants who come by and say, we can give everyone the water they need. So to insure fair distribution and equity in watershed governance, all working rules consider more efficient use of the supply: promoting water saving devices and closing loops by recycling (more with less), optimizing the use of energy (less water lost as a coolant and feeder stock in utilities and industry), optimizing the use of material flows (less water lost as an ingredient and medium for catalysis in chemical and food industries), minimizing waste generation (less water lost as a dilutor of harmful residues), and maximizing «cascading» uses (water of varying qualities assigned to their most appropriate use). Efficiency by itself is nowhere near the complete picture. Cultural needs may be inefficient. But, appropriate technology—from drip irrigation to adopting the least water intensive industrial process—is a crucial tool.

Incentives: Watershed accounting looks at each cashflow and waterflow and decides if the money spent can be justified. This conceptual tool looks at the kind of temptation or incentive that money provides: perverse, harmonious or punitive. A perverse incentive is, for instance, subsidizing the energy cost of pumping water from an aquifer faster than it can be replenished. Or paying to rebuild a town in a floodplain, when its cheaper to move the whole town inland. A true incentive is allowing a farmer to sell any water from his vested right that he conserves through changing his irrigation practices. A disincentive is financially penalizing or closing down a polluter that degrades water quality used for drinking. Listing rules within these three categories (perverse, true or dis-incentives) forces healing into the practical realm. First and foremost, rid the watershed community of perverse incentives. Second, encourage and find new incentives. Third, restrict disincentives to violations of the clear rules of access, use, re-use and «security of the minimum.»

Allaying fears: What is “clean” water? What is “adequate” supply? What is “harm” or “damage” from pollution, acid rain, or up-stream watershed alterations that cause downstream floods? Judging risk is not easy. Its hard to remain skeptical, but not cynical, of those who claim its all fine (don’t worry). Does the bacteria enterococcus cause sickness in salt water, when the studies have only been done in freshwater lakes? How much enterococcus is dangerous? Given imperfect knowledge, how much to pay for what technology to reduce enterococcus along the shoreline? Can we allow one infection for every thousand swimmers or one in ten thousand? But my kids are on the beach! Is the politico exploiting local fears so he can appear as the white knight that will save the children? Or has he made a deal with the engineering firms that will profit from “solving” what may be a non-problem? Or , is the health department in need of more federal funds to keep the bureaucracy humming and enterococcus is a way to drum up financing? Or is the department doing its duty to protect the public health? Is the media looking for dramatics? Is the issue smoke-and-mirrors, dueling experts, talking heads or a real risk? And who really understands the “risk assessment” models of successive approximation, correlation and regression, extreme or central values that allegedly prove safety?

Once again, the “truth issue” brings citizens to shadow governments and skillful leaders who respect water first and foremost, and spend time understanding its wily ways. In my experience, intimacy with the truth of water rarely insures success in the political arena. But, a combo of empirical hydro-truths and a sense of fairness can hold sway. For instance, the environmental justice movement, a movement among minorities whose watersheds became the dumping grounds for water-borne pollutants, gained strength by combining meticulous water quality data, epidemiology, and ethical arguments for civil rights. There are dozens of similar stories from the Clearwater yacht on the Hudson that took water samples to Love Canal moms.

Rules for changing rules: In Africa, many citizens told me: «We like America. When you change leaders, no one gets killed.» The last tool rests on wisdom, a deep wisdom. How to educate leaders to change rules without bloodshed? How to change rules without installing the internal desire for revenge? Watershed governance falters when there are no rules for changing rules. Modifying the ownership of water, communal holding rights, and the access and time of use rules are essential conflict resolution arenas for sustainable watersheds. When the existing rules are obsolete, negotiations become tedious and ugly. Complex and touchy issues are pushed aside (“We’ll deal with that later.”) But, rules to change rules are as important as knowing that cutting trees will cause floods in the future. A tool to remember.

Water-watchers at the Holy Spring

Let the most absent-minded of men be plunged into the deepest reveries…..and he will infallibly lead you to water, if water there be in that region….meditation and water are wedded forever.

— Melville

There are certain watery places where understandings and healing are easier. Springs are classic. Here, the essence of watershed governance delightfully displays itself. The spring is a specific place; watershed governance is always in unique geographies. The spring is a literal source of life; so is the ability of humans to govern themselves with generosity. The spring, coming from underground, makes one contemplate the unseen and unknown; major skills in the wily politics of waterflows and human desires. Springs tend to have special waters, healing waters, and healing plants; humans like to gather at them and make special side-trips or pilgrimages to them. Springs and community governance carry unique history (“remember what happened at the spring in 1876?”). Even when not physically at the spring, springs become images of life-giving, and reverence; memories that encourage humans to meditate on their dreams and what they will accept in life. Springs re-enforce the value of water-watching, of placing water first in the resolution of differences. Springs bring humans back to basics.

To end, the best hydro-citizens are water-watchers. They love to discuss rainfall or the meanderings of their river, big hale storms and how exhaust fumes mix with fog. They love to bicker about who’s sucking up how much water at what price or how many parts per billion are dangerous. Without maniacal water watching and daily palaver, water and governance have a hard time mixing. For all watershed governance rests on inter-woven life-support; on water’s qualities as well as quantities; on appreciating how flexibility harmonizes with hydro-whimsy. Changing the direction of soul flow as well as water and cash flow requires tremendous dedication and energy. Michelet, an eighteenth century Utopian, understood water’s ability to mix what humans might want kept separate. He wrote: «Religion, education, government. These are the same word.» And, then, perhaps, he took a hot bath.